In the complex world of finance, deciphering the true worth of an asset can often feel like navigating a maze. This is where the concept of “fair value” emerges as a beacon of clarity, offering a glimpse into the actual market value of an asset at any given point in time. Imagine a scenario where you’re evaluating a company’s financial health, and every asset on its balance sheet reflects not just a historical cost but its real market value; this is the transformative power of fair value, playing a pivotal role in financial reporting.

The application of fair value isn’t limited to just presenting shiny numbers on a report. It’s a dynamic tool that influences critical financial decisions, such as assessing impairments and structuring fair value hierarchies. Understanding how fair value is used in financial reporting, especially in these areas, can be the difference between making informed investment decisions and wandering in financial ambiguity. By decoding these applications, we can gain deeper insights into a company’s true financial landscape and make more strategic choices in our own financial journeys.

Importance of Fair Value in Financial Reporting

In financial reporting, fair value serves as the bridge between raw accounting figures and the real economic worth of an asset or liability. By reflecting the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction at the measurement date, fair value injects transparency into financial statements. This allows investors, analysts, and management to gauge the true financial health of an organization without relying solely on historic book values. As markets evolve rapidly, historical cost figures can drift far from current market conditions, whereas fair value aligns reporting with present-day realities.

Moreover, fair value forms the backbone of robust stock valuation practices. Consistent and transparent fair value measurements enable stakeholders to compare companies operating in different industries or jurisdictions on an apples-to-apples basis. They also reduce information asymmetry by disclosing the assumptions and inputs used, ranging from quoted market prices to complex valuation models. When questions arise. How is fair value used in financial reporting (impairments, fair value hierarchies)? The answer lies in its role as a dynamic, market-reflective measure, crucial for informed analysis and strategic decision-making in today’s fast-moving financial landscape.

Application of Fair Value in Asset Valuation

Fair value plays an essential role in valuing a wide array of assets, from marketable securities and investment properties to intangible assets like trademarks and customer relationships. It requires evaluation of current market data, including comparable transactions, quoted prices in active markets, and, when those aren’t available, alternative valuation techniques such as discounted cash flow analyses. This process ensures that asset valuations remain reflective of prevailing market conditions rather than outdated historical acquisition costs.

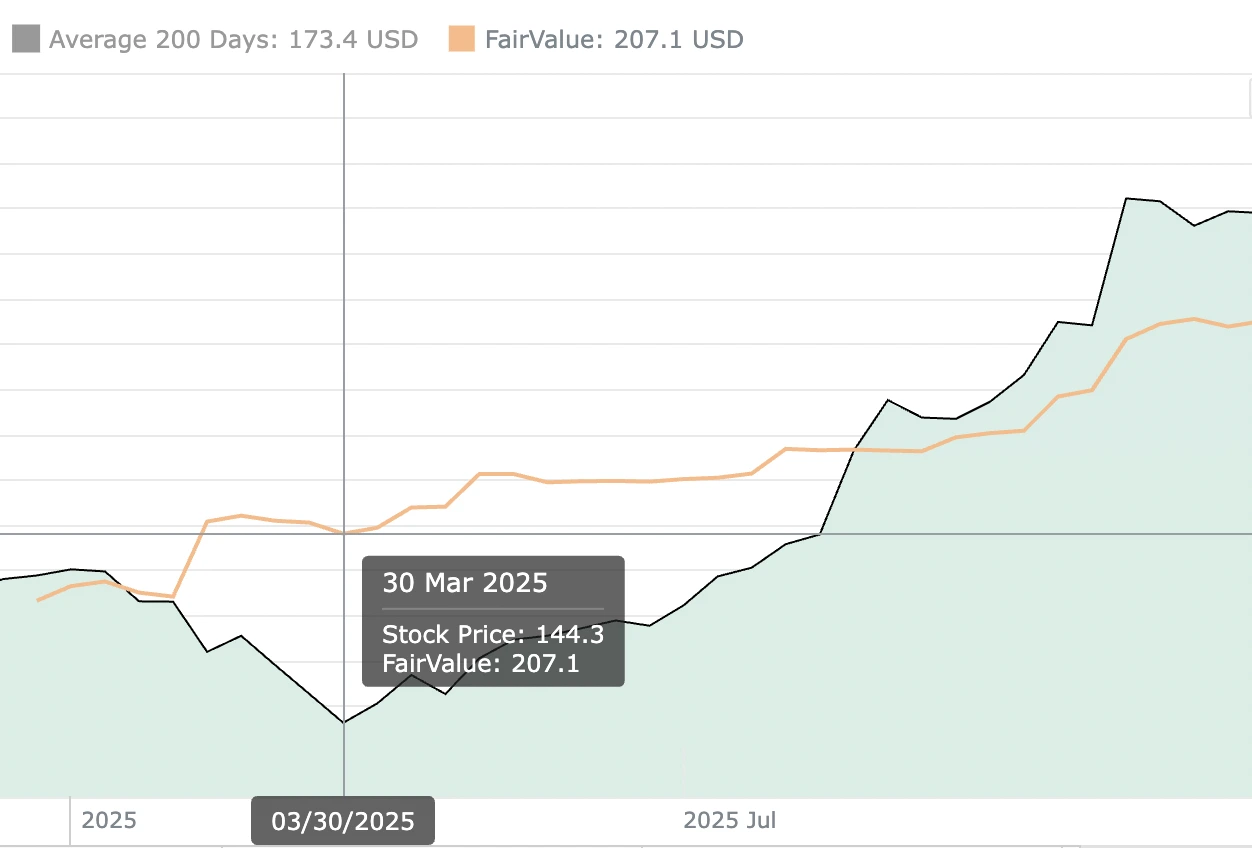

In practice, companies often apply fair value during periodic revaluations of non-current assets, stock valuation reviews, and financial instrument measurements. For instance, an investment property that has appreciated due to market demand will be restated on the balance sheet at its new fair value, boosting equity and providing clearer signals to investors. Beyond balance sheet revaluations, fair value inputs feed directly into financial ratios and performance indicators, influencing credit decisions, lending covenants, and investment strategies. The transparent disclosure of methodologies and key assumptions further enhances comparability across entities and industries.

Fair Value vs. Historical Cost Accounting

Under historical cost accounting, assets are recorded and carried at the original purchase price minus accumulated depreciation. While this method is objective and verifiable, it often fails to capture the current economic realities. Market prices fluctuate, and the historical cost may become arbitrarily disconnected from an asset’s true worth. Consequently, financial statements prepared under this model might portray a company’s net worth inaccurately, leading to suboptimal decisions by stakeholders.

Conversely, fair value accounting updates asset and liability measurements to reflect current market conditions. This approach offers timelier insights but introduces complexity and subjectivity, especially when market data is scarce. Organizations must carefully choose between these models based on their objectives: historical cost provides consistency and reliability, while fair value delivers relevance and responsiveness. Many jurisdictions allow a mixed-model approach, where financial instruments and investment properties use fair value, while other assets remain on a historical cost basis, striking a balance between verifiability and economic accuracy.

Explore our most popular stock fair value calculators to find opportunities where the market price is lower than the true value.

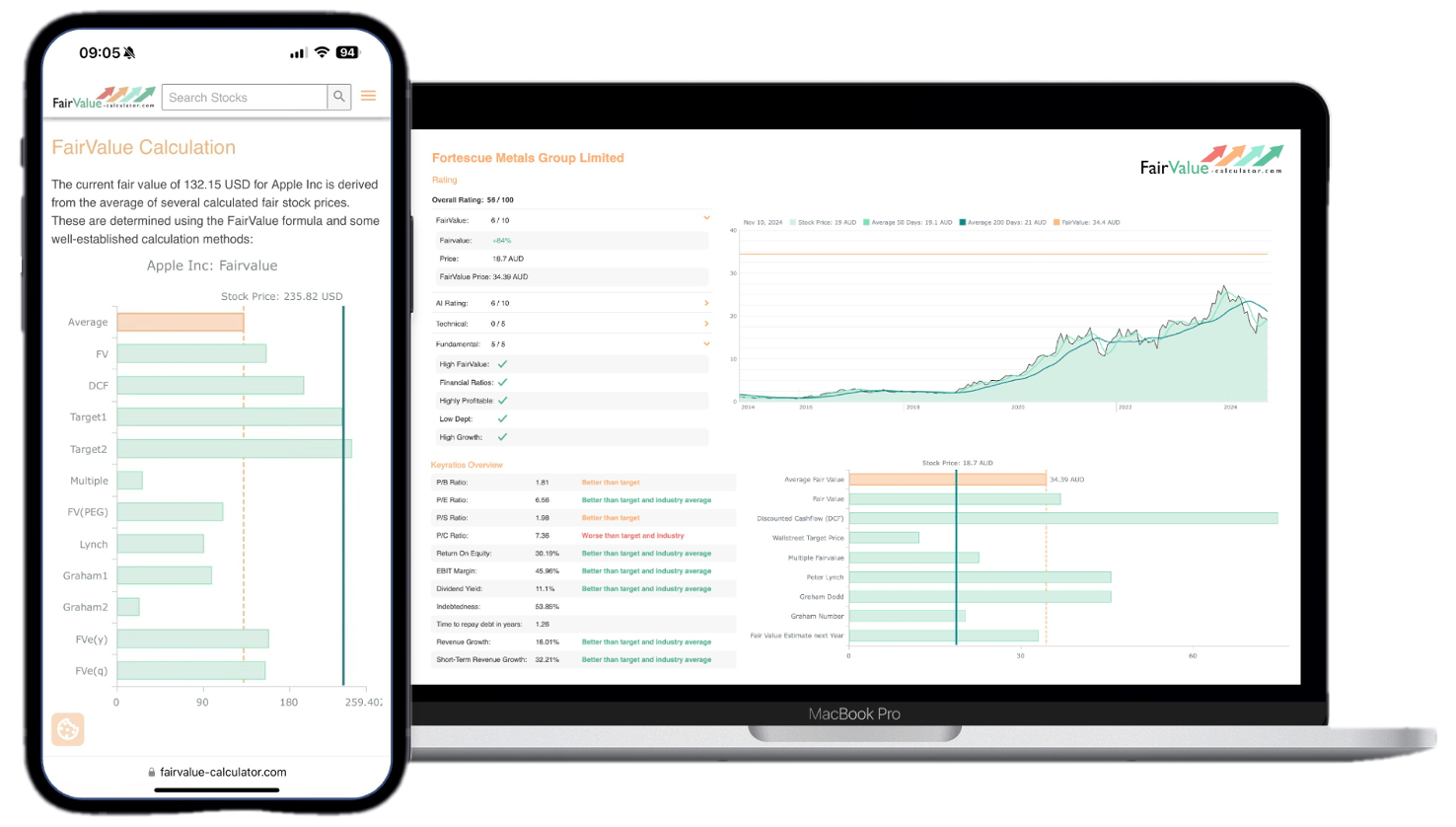

- Peter Lynch Fair Value – Combines growth with valuation using the PEG ratio. A favorite among growth investors.

- Buffett Intrinsic Value Calculator – Based on Warren Buffett’s long-term DCF approach to determine business value.

- Buffett Fair Value Model – Simplified version of his logic with margin of safety baked in.

- Graham & Dodd Fair Value – Uses conservative earnings-based valuation from classic value investing theory.

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value – Learn the core difference between what a company’s really worth and what others pay.

- Intrinsic Value Calculator – A general tool to estimate the true value of a stock, based on earnings potential.

- Fama-French Model – For advanced users: Quantifies expected return using size, value and market risk.

- Discount Rate Calculator – Helps estimate the proper rate to use in any DCF-based valuation model.

Fair Value Impairments: Recognizing and Measuring

Impairment testing ensures that assets are not carried on the balance sheet at amounts exceeding their recoverable fair value. When market conditions deteriorate or an asset’s performance declines, companies must compare its carrying amount to its estimated fair value. If the carrying amount is higher, an impairment loss is recognized, reflecting the decrease in recoverable value. This process provides timely recognition of declines in asset worth, rather than waiting for a disposal or sale.

Measuring fair value impairments often involves estimating future cash flows and discounting them at an appropriate rate. The choice of discount rate, growth assumptions, and market inputs can materially influence the impairment loss recorded. Impairments pertaining to goodwill, indefinite-lived intangibles, and goodwill acquired in business combinations are particularly scrutinized due to their sensitivity to valuation assumptions. Transparent disclosure of methods and key assumptions is crucial to bolster stakeholder confidence and prevent earnings management.

Factors Influencing Fair Value Measurements

Fair value hinges on several critical factors. First and foremost is market data availability: quoted prices in active markets provide the most reliable input. When active markets are absent, companies turn to observable inputs such as recent transactions of similar assets. Failing that, unobservable inputs, management’s own assumptions about future cash flows and risk adjustments, must be used. The reliability of fair value measurements diminishes as the reliance on unobservable inputs increases.

Additional influences include macroeconomic factors like interest rates, inflation, currency fluctuations, and industry-specific trends. For example, in volatile commodity markets, fair values can swing dramatically in short periods, requiring frequent revaluations. Corporate actions, regulatory changes, and technological disruptions can also reshape market sentiments and alter fair value estimates. Consequently, practitioners must stay attuned to evolving market conditions and update valuation models to preserve accuracy and relevance.

💡 Discover Powerful Investing Tools

Stop guessing – start investing with confidence. Our Fair Value Stock Calculators help you uncover hidden value in stocks using time-tested methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Benjamin Graham’s valuation principles, Peter Lynch’s PEG ratio, and our own AI-powered Super Fair Value formula. Designed for clarity, speed, and precision, these tools turn complex valuation models into simple, actionable insights – even for beginners.

Learn More About the Tools →Fair Value Hierarchy Levels

The fair value hierarchy organizes inputs used into three levels based on observability and reliability, promoting consistency in measurement.

Level 1 relies on quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities. Level 2 uses observable inputs other than Level 1 prices, such as quoted prices for similar items or market‐corroborated inputs. Level 3 involves unobservable inputs, management’s best estimates using internal data and valuation models. The hierarchy’s structure ensures that financial statements clearly communicate the degree of subjectivity in fair value measurements.

Challenges in Implementing Fair Value Measurements

Implementing fair value methodologies can pose significant challenges. Obtaining reliable market data for unique or illiquid assets is often difficult, forcing greater reliance on judgment and valuation models. This increases the risk of estimation errors and potential bias. Auditors and regulators may question management’s assumptions, leading to contentious negotiation over discount rates, growth projections, and hurdle rates.

Operationally, frequent revaluations demand robust governance, specialized personnel, and advanced valuation tools. Smaller entities may struggle with the costs and complexity involved, while larger organizations must coordinate valuations across diverse asset classes and global units. Ensuring consistency in fair value approaches and maintaining thorough documentation of inputs and methodologies are critical to overcoming these obstacles.

Transparency and Disclosure Requirements in Fair Value Reporting

Regulatory frameworks like IFRS 13 and ASC 820 mandate extensive disclosures around fair value measurements. Companies must explain the valuation techniques used, classify inputs within the fair value hierarchy, and provide sensitivity analyses showing how changes in assumptions could impact valuations. For Level 3 measurements, detailed reconciliation of opening and closing balances, plus disclosure of significant unobservable inputs, is required.

Clear, comprehensive disclosures help users of financial statements assess the reliability of fair value estimates and understand potential valuation risks. By presenting this information in notes to the financial statements, companies foster trust and facilitate better decision-making by investors, creditors, and other stakeholders.

Case Studies: Real-world Applications of Fair Value

One notable example involves a multinational real estate firm that applies fair value to its investment properties each quarter. By engaging external valuation experts and leveraging recent transaction data, the firm ensures that its balance sheet reflects current market trends. This approach not only improves transparency but also supports strategic portfolio management decisions, such as acquisitions, divestitures, and refinancing arrangements.

Another case centers on a technology company that acquired several startups, recording significant goodwill on its balance sheet. Through annual impairment testing, the company identified underperforming cash-generating units and recognized impairment losses based on discounted cash flow models. These impairments provided stakeholders with timely insights into acquisition performance and guided management’s decisions on restructuring and resource allocation.

Conclusion: Embracing Fair Value for Informed Financial Decision-making

Fair value transforms static accounting figures into dynamic reflections of real-time market conditions, enhancing the relevance and comparability of financial statements. By understanding how fair value is used in financial reporting (impairments, fair value hierarchies), stakeholders gain clearer insights into asset health and potential risks.

While implementation challenges and judgment calls remain, rigorous governance, transparent disclosures, and adherence to established frameworks ensure that fair value serves as a reliable compass for strategic decision-making. Embracing fair value equips investors, managers, and regulators with the tools to navigate today’s complex financial landscape with confidence.