In the complex world of finance and investing, clarity can often seem elusive. The term “fair value” is frequently thrown around in discussions, yet many find themselves puzzled by its true meaning and significance. Imagine having the ability to peer beyond market fluctuations and see an asset’s worth with precision and confidence. That’s the promise fair value offers. As we navigate an economy laden with unpredictable turns, understanding fair value not only helps investors but also equips businesses to make informed decisions that align with their financial goals.

Understanding “What is fair value?” becomes more than just a quest for knowledge, it’s a tool for empowerment. By dissecting this concept, we open the door to a clearer comprehension of assets and investments. Whether you’re a seasoned investor, a business owner, or someone with a keen interest in financial markets, grasping fair value can transform your approach to trading, risk management, and strategic planning. Let’s delve into this concept and uncover why it holds such vital importance in today’s economic landscape.

The Basics of Fair Value

At its core, fair value represents an unbiased estimate of an asset’s worth under normal market conditions. Unlike book value, which relies on historical cost, fair value adjusts to reflect current market dynamics. A common question that arises is What is “fair value”? Simply put, it is the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. This definition highlights two essential components: an orderly transaction and the perspective of market participants.

Fair value measurement encompasses a wide array of assets and liabilities, from publicly traded securities to real estate holdings and complex financial derivatives. It integrates observable market data, such as quoted prices in active markets, along with unobservable inputs, like management assumptions. Entities often rely on valuation techniques, discounted cash flows, comparables, or option pricing models, to triangulate a fair value estimate. By grounding valuations in current data rather than historical book entries, fair value offers a more dynamic reflection of an asset’s economic potential and risk profile.

Understanding the basics of fair value equips stakeholders with a benchmark that aligns accounting figures with reality. Investors gauge the attractiveness of potential investments by comparing market prices against fair value estimates. Companies use fair value to allocate purchase price in acquisitions, assess impairments, and manage financial instruments. As markets evolve and information becomes more accessible, fair value remains a cornerstone for transparent and relevant financial reporting, bridging the gap between numbers on a balance sheet and actual economic worth.

The Significance of Fair Value in Finance

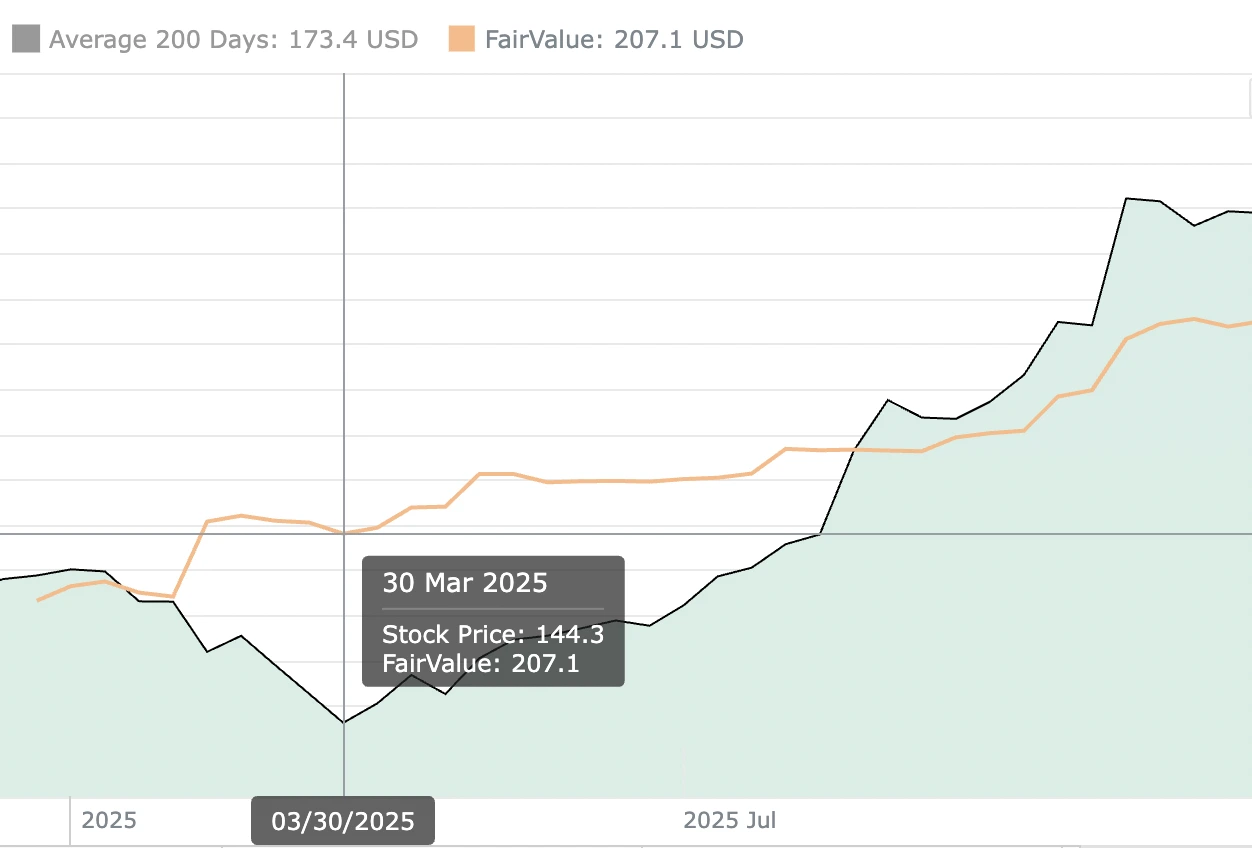

The significance of fair value in finance extends beyond accounting entries; it underpins decision-making at every level. For investors, fair value is a compass guiding them toward undervalued or overvalued assets. By comparing a company’s market price to its estimated fair value, investors can identify buying opportunities or exercise caution when prices exceed intrinsic worth. This approach mitigates the inherent risks of market speculation and promotes a disciplined, long-term investment strategy.

Within corporations, fair value drives operational and strategic choices. When evaluating potential acquisitions, management assesses target companies by estimating the fair value of identifiable assets and liabilities. This granular analysis informs negotiation strategies, informs due diligence efforts, and helps determine goodwill. Post-acquisition, regular fair value measurements ensure that any impairments or reversals are promptly recognized, leading to timely corrective actions and transparent reporting to stakeholders.

Regulators and standard-setters also emphasize fair value for its ability to enhance comparability across entities and industries. By standardizing measurement techniques, users of financial statements gain greater confidence in the consistency and reliability of reported figures. This comparability fosters a level playing field, where lenders, insurers, and market analysts can better assess creditworthiness, risk exposures, and capital adequacy. As global markets become more intertwined, fair value contributes to financial stability by providing a realistic snapshot of financial positions.

Explore our most popular stock fair value calculators to find opportunities where the market price is lower than the true value.

- Peter Lynch Fair Value – Combines growth with valuation using the PEG ratio. A favorite among growth investors.

- Buffett Intrinsic Value Calculator – Based on Warren Buffett’s long-term DCF approach to determine business value.

- Buffett Fair Value Model – Simplified version of his logic with margin of safety baked in.

- Graham & Dodd Fair Value – Uses conservative earnings-based valuation from classic value investing theory.

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value – Learn the core difference between what a company’s really worth and what others pay.

- Intrinsic Value Calculator – A general tool to estimate the true value of a stock, based on earnings potential.

- Fama-French Model – For advanced users: Quantifies expected return using size, value and market risk.

- Discount Rate Calculator – Helps estimate the proper rate to use in any DCF-based valuation model.

Methods for Determining Fair Value

Accurately determining fair value requires the application of standardized valuation techniques that balance observable market data with professional judgment. The three primary approaches—market, income, and cost—offer flexibility in capturing the unique characteristics of different assets and liabilities. Each method leverages specific data inputs and analytical frameworks to arrive at a credible estimate.

Selection of the appropriate method depends on the nature of the asset, availability of data, and the level of estimation uncertainty. Entities often prioritize observable inputs from active markets, while relying on professional expertise to interpret unobservable information. By adhering to a structured hierarchy of inputs and transparent documentation, organizations can substantiate fair value measurements and withstand audit scrutiny.

Market Approach

The market approach derives fair value by referencing prices and other market data for identical or comparable assets. This method is highly reliable when active, liquid markets exist. For example, publicly traded equities and widely traded commodities lend themselves to straightforward market transactions that establish clear price points. Practitioners adjust for differences in asset condition, location, or contractual terms to ensure comparability. When adequate market data is available, the market approach yields objective fair value estimates with minimal subjectivity involved.

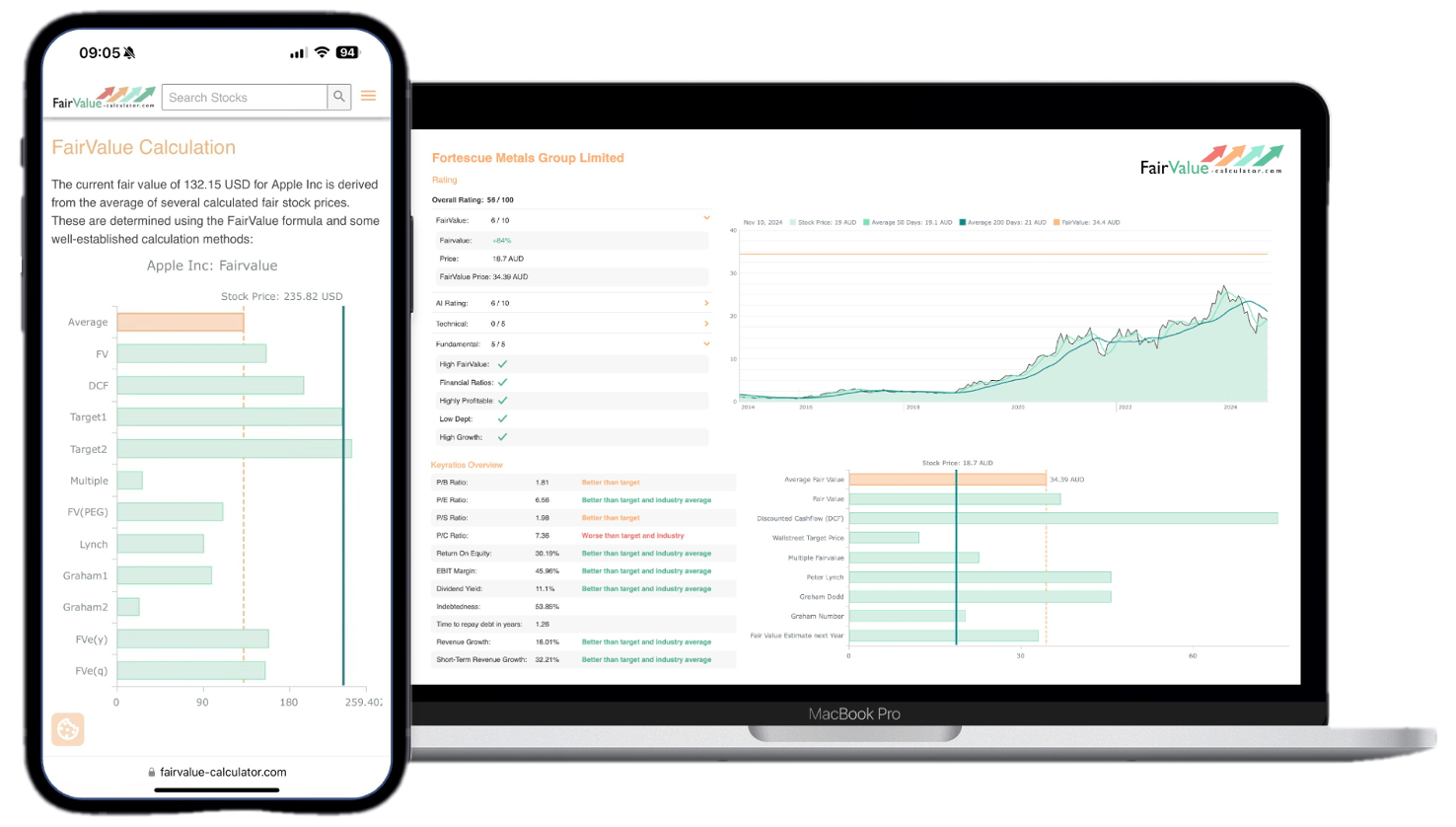

💡 Discover Powerful Investing Tools

Stop guessing – start investing with confidence. Our Fair Value Stock Calculators help you uncover hidden value in stocks using time-tested methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Benjamin Graham’s valuation principles, Peter Lynch’s PEG ratio, and our own AI-powered Super Fair Value formula. Designed for clarity, speed, and precision, these tools turn complex valuation models into simple, actionable insights – even for beginners.

Learn More About the Tools →However, in less liquid markets, comparable transactions may be scarce, necessitating significant adjustments. Analysts must then exercise caution, validating the relevance of each transaction and ensuring that adjustments reflect economic realities. Despite these challenges, when applied correctly, the market approach offers the most direct link between fair value estimates and actual market activity, enhancing transparency for financial statement users.

Income Approach

The income approach focuses on the present value of future cash flows an asset is expected to generate. By discounting projected earnings or cost savings at an appropriate rate, this method captures the asset’s intrinsic value over its useful life. Key inputs include reliable cash flow forecasts, discount rates reflecting market risk, and growth assumptions. The discounted cash flow (DCF) model is the most widely recognized application of this approach.

While the income approach can accommodate assets without active markets, it is sensitive to underlying assumptions. Small changes in discount rates or cash flow projections can yield significantly different fair value outcomes. To bolster credibility, analysts conduct sensitivity analyses and cross-verify results with alternative valuation models. This method is particularly useful for valuing intangible assets, private companies, and project-specific investments where market comparables are unavailable.

Cost Approach

The cost approach estimates fair value based on the current replacement cost of an asset, less depreciation or obsolescence. This technique is often applied to tangible assets like property, plant, and equipment. By calculating the cost to replicate the asset’s service capacity at today’s prices and adjusting for physical deterioration or functional obsolescence, practitioners derive a fair value benchmark grounded in underlying asset utility.

Though straightforward, the cost approach may not fully capture an asset’s earning potential or strategic synergies. It is best suited for specialized or unique assets lacking active markets or predictable income streams. When integrated with other methods, the cost approach offers a complementary perspective, reinforcing the robustness of the overall fair value measurement.

Fair Value vs. Market Value

Fair value and market value both revolve around pricing, but they serve distinct purposes. Market value refers to the actual trading price in an active market at a given time, reflecting supply and demand dynamics. Fair value, on the other hand, represents an estimate of what an arm’s-length transaction would yield under ideal market conditions. While market value is backward-looking and transactional, fair value aims to be a forward-looking, theoretical benchmark.

Consider a thinly traded stock: its quoted market price may not reflect the true willingness of buyers and sellers to transact. Fair value analysis would adjust that quoted price to account for lack of liquidity, transaction costs, and market volatility. Conversely, in highly liquid markets, such as major currency pairs, the distinction between market and fair value is minimal, as active trading ensures that quoted prices align closely with theoretical fair value.

Understanding these nuances helps users of financial statements reconcile price differences. Investors comparing fair value disclosures to actual market data can identify potential distortions arising from market inefficiencies. For businesses, recognizing the gap between market and fair values can guide hedge strategies, capital allocation, and performance evaluations, ensuring that financial decisions rest on realistic valuations rather than transient price swings.

Fair Value Accounting Standards

Global accounting frameworks, including IFRS 13 and ASC Topic 820, codify fair value measurement principles to foster consistency and transparency. IFRS 13 provides a single source of guidance under International Financial Reporting Standards, while ASC 820 serves as its counterpart in U.S. GAAP. Both standards emphasize a three-level hierarchy of inputs, from Level 1 observable market prices to Level 3 unobservable inputs that rely heavily on management judgment.

Under these standards, entities must maximize use of observable inputs and disclose significant valuation assumptions. Required disclosures include the valuation methods, input hierarchy levels, and sensitivity analyses for Level 3 measurements. Regulators and auditors scrutinize these disclosures to ensure that fair value estimates are supported by robust evidence and that risks of managerial bias are minimized. Compliance with fair value accounting standards not only enhances the credibility of financial statements but also aligns reporting practices across jurisdictions, facilitating cross-border investment and analytical comparability.

Fair Value in Investment Decision Making

Investors integrate fair value estimates into fundamental analysis to assess whether securities are undervalued or overvalued. By deriving a fair value estimate, often via discounted cash flow models or comparables, analysts establish a target price that guides buy, hold, or sell decisions. This disciplined framework reduces reliance on market sentiment and speculative trends, anchoring investment strategies in objective valuation grounds.

Institutional investors and hedge funds frequently publish research reports that highlight fair value discrepancies. When market price dips below fair value, they may initiate long positions, anticipating a price correction. Conversely, if market price exceeds fair value, short-selling opportunities emerge. Retail investors can also use fair value calculators and brokerage research tools to inform portfolio adjustments. Ultimately, by embedding fair value into investment decision making, market participants benefit from a systematic approach that marries quantitative rigor with qualitative insights.

Challenges in Applying Fair Value

Despite its advantages, applying fair value is not without challenges. One major hurdle is the reliance on unobservable inputs for Level 3 measurements. These inputs, such as internal forecasts or proprietary valuation models, introduce subjectivity and increase the risk of bias. Management judgments about discount rates, growth projections, and comparability adjustments can significantly sway fair value estimates, potentially obscuring the clarity the measurement aims to provide.

Another challenge lies in market illiquidity and volatility. In thinly traded or distressed markets, observable data may be scarce or unreliable. Analysts must judiciously select proxies and validate assumptions, balancing the need for realistic valuations with the limitations of available information. Regulatory scrutiny has intensified around fair value disclosures, requiring robust documentation and increased transparency to withstand audit and investor examination.

Moreover, frequent fair value remeasurements can amplify earnings volatility in financial statements. Companies holding large portfolios of financial instruments may report significant fair value gains or losses within single reporting periods, generating unpredictability in key performance indicators. Stakeholders must therefore interpret fair value-driven fluctuations in light of broader business fundamentals and market conditions.

The Impact of Fair Value on Financial Reporting

Fair value measurement dramatically reshapes financial reporting by aligning recorded balances with contemporary economic realities. Assets and liabilities reflected at fair value provide stakeholders with timely insights into potential gains, losses, and risk exposures. This stands in contrast to historical cost accounting, which may obscure underlying economic shifts until realized through transaction events like sale or impairment.

Fair value’s impact is especially pronounced in industries reliant on financial instruments, banking, insurance, and investment management. Here, loan portfolios, derivatives, and trading securities are revalued each reporting period. Transparent fair value reporting empowers investors to gauge institutions’ exposure to market risks, credit quality, and liquidity conditions. Even nonfinancial sectors benefit: fair value accounting for acquired intangibles and property ensures that balance sheets accurately represent the current value drivers and obligations.

Nonetheless, the move toward fair value reporting demands rigorous internal controls and valuation governance. Companies establish dedicated valuation teams, engage external specialists, and periodically validate model inputs. These measures strengthen data integrity, mitigate biases, and uphold regulatory compliance. In doing so, financial statements not only reflect fair value measurements but also engender confidence in the quality and reliability of reported results.

Fair Value’s Role in Risk Management

Fair value plays a pivotal role in enterprise risk management by providing real-time metrics on asset and liability fluctuations. Risk managers monitor fair value changes to identify emerging exposures, such as interest rate risk in bond portfolios or credit risk in loan books. By quantifying potential losses under current market conditions, organizations can proactively adjust hedging strategies, capital buffers, and liquidity reserves.

Liquidity risk management heavily relies on fair value inputs. During market stress, rapid shifts in fair values signal tightening liquidity or widening credit spreads. Companies equipped with fair value reporting systems can stress-test portfolios, simulate adverse scenarios, and develop contingency plans. This foresight strengthens resilience, enabling swift responses to market shocks and regulatory requirements.

Moreover, fair value underpins enterprise-wide risk metrics like Value at Risk (VaR) and Economic Capital. These models aggregate fair value positions across business lines, producing comprehensive risk profiles. Senior management and boards use these insights to set risk appetite, allocate capital efficiently, and ensure that strategic initiatives remain within acceptable risk thresholds. In this way, fair value transforms raw financial data into actionable intelligence, fortifying risk governance frameworks and supporting sustainable growth.

Conclusion: Harnessing the Power of Fair Value

Fair value stands as a cornerstone of transparent, relevant financial reporting and prudent decision-making. By reflecting current market conditions, it transforms static balance sheet entries into dynamic indicators of economic reality. Investors, analysts, and corporate leaders all benefit from its insights.

While challenges exist, particularly around subjectivity and market data limitations, robust valuation governance and standardized accounting standards help mitigate these risks. Ultimately, mastering fair value equips stakeholders with the clarity and confidence needed to navigate complex financial landscapes and drive long-term success.