In the intricate world of finance, understanding the true worth of an asset is akin to unraveling a complex puzzle. Each piece, though significant in isolation, must seamlessly connect with others to reveal the full picture. For investors, analysts, and businesses alike, this clarity forms the backbone of making informed decisions. Enter the realm of fair value models, a trio of powerful methodologies that serve as guiding stars on this journey. The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method delves into future cash projections like a time traveler forecasting prosperity, whereas the Comparables approach stands as a contemporary mirror, reflecting market perceptions. Meanwhile, the Asset-Based model grounds itself firmly in present realities.

Yet, how does one navigate these distinct paths to discern the most fitting road to take? In this blog post, we embark on an enlightening exploration of the comparison of fair values by different models, DCF vs comparables vs asset-based. By dissecting each model’s core tenets, strengths, and limitations, you’ll gain the insight needed to select the most appropriate method for your valuations. Whether you’re seeking to untangle a corporate balance sheet or simply aiming to enhance your financial acumen, this deep dive promises to illuminate the various shades of fair value assessment. Prepare to enrich your understanding and empower your strategic decisions.

Understanding Fair Value Models

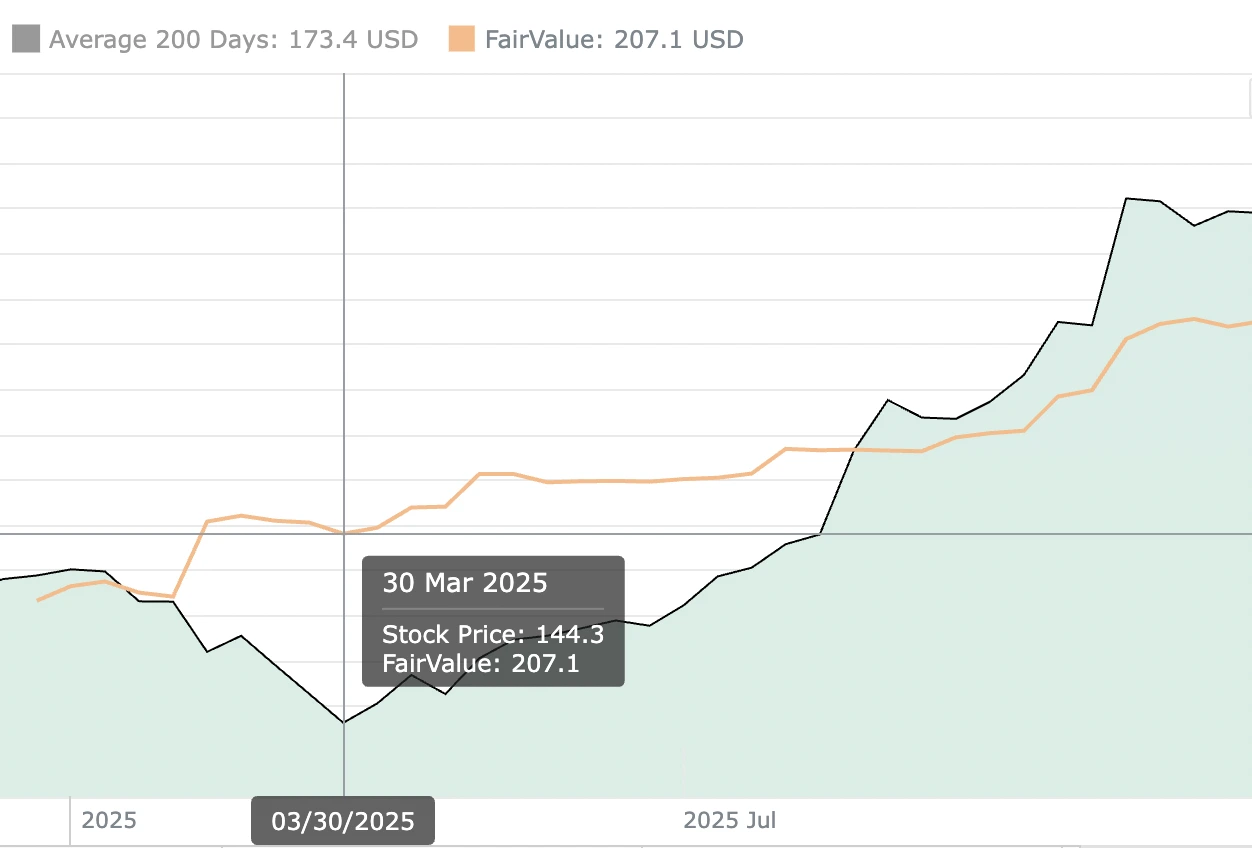

Fair value models are methodologies designed to estimate an asset’s intrinsic worth by incorporating various inputs such as future cash flows, market comparables, and tangible asset balances. These frameworks help stakeholders assess whether a security, business unit, or entire company is undervalued, overvalued, or trading at an appropriate price. In practice, adopting the right valuation model hinges on the nature of the asset, the availability of reliable data, and the strategic decision at hand, be it investment, merger and acquisition, or financial reporting.

Within the broad context of valuation, three primary models stand out: the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) approach, the Comparables method, and the Asset-Based model. Each framework carries a distinct philosophy. DCF focuses on the time value of money by forecasting and discounting future cash flows, Comparables gauge value relative to peer companies or transactions in the marketplace, and Asset-Based models emphasize the present value of a company’s tangible and intangible assets. Understanding their unique mechanics is crucial for anyone involved in corporate finance, equity research, or private equity due diligence.

Given the inherent complexities of each model, a head-to-head comparison of fair values by different models (DCF vs comparables vs asset-based) can yield different valuations for the same asset. Reconciling these differences involves examining the assumptions and inputs driving each method. Ultimately, a comprehensive valuation exercise may leverage multiple models in tandem, providing a valuation range rather than a single point estimate. This holistic perspective equips decision-makers with a more robust understanding of potential upside or downside scenarios.

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method

The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method is a forward-looking valuation technique that estimates an asset’s present value by projecting its future cash flows and discounting them back to today’s terms. This model treats money as time-sensitive, recognizing that a dollar earned in the future is worth less than one in hand today. By incorporating discount rates that reflect risk and opportunity cost, the DCF model provides a theoretically sound measure of intrinsic value.

Despite its conceptual elegance, the DCF method demands rigorous forecasting and careful selection of discount rates. Small deviations in growth projections, terminal value assumptions, or discount rates can lead to wide swings in estimated value. Consequently, analysts must thoroughly justify each assumption and conduct sensitivity analyses to gauge valuation robustness. In practice, DCF is most effective for businesses with predictable cash flows, solid growth trajectories, and transparent operating metrics.

Explore our most popular stock fair value calculators to find opportunities where the market price is lower than the true value.

- Peter Lynch Fair Value – Combines growth with valuation using the PEG ratio. A favorite among growth investors.

- Buffett Intrinsic Value Calculator – Based on Warren Buffett’s long-term DCF approach to determine business value.

- Buffett Fair Value Model – Simplified version of his logic with margin of safety baked in.

- Graham & Dodd Fair Value – Uses conservative earnings-based valuation from classic value investing theory.

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value – Learn the core difference between what a company’s really worth and what others pay.

- Intrinsic Value Calculator – A general tool to estimate the true value of a stock, based on earnings potential.

- Fama-French Model – For advanced users: Quantifies expected return using size, value and market risk.

- Discount Rate Calculator – Helps estimate the proper rate to use in any DCF-based valuation model.

Core Principles of DCF

At its heart, the DCF model rests on two fundamental principles: the time value of money and the risk–return tradeoff. By forecasting free cash flows, cash available after operating expenses, taxes, and capital expenditures, the model captures the cash-generating potential of an asset or business. These cash flows are then discounted at a rate that accounts for the risk profile of the investment, often represented by the weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

In essence, DCF transforms expected future benefits into an equivalent lump sum today. Analysts typically forecast cash flows over a discrete period (five to ten years) before calculating a terminal value to capture all subsequent cash flows. This dual-phase approach balances the need for detailed near-term forecasts with a simplified long-term assumption. By adhering to these core principles, the DCF model strives to deliver an intrinsic value estimate grounded in economic reality.

Strengths of DCF Model

The DCF method offers several compelling advantages. First, it directly ties valuation to underlying cash flows, making it a fundamentally sound approach for businesses with stable and predictable earnings. Second, the model facilitates scenario analysis and sensitivity testing, allowing analysts to examine how changes in growth rates, discount rates, or other inputs affect valuation outcomes. Third, by explicitly incorporating risk through the discount rate, DCF provides a transparent mechanism to reflect the uncertainty embedded in future cash flows.

Moreover, DCF doesn’t rely on market multiples, which can be distorted by temporary market sentiment or industry cycles. Instead, it focuses on the asset’s own operational performance. This independence renders DCF particularly valuable in markets where trading multiples are highly volatile or when no comparable companies exist. For long-term investors seeking to align valuations with fundamental value drivers, DCF remains a gold standard methodology in corporate finance.

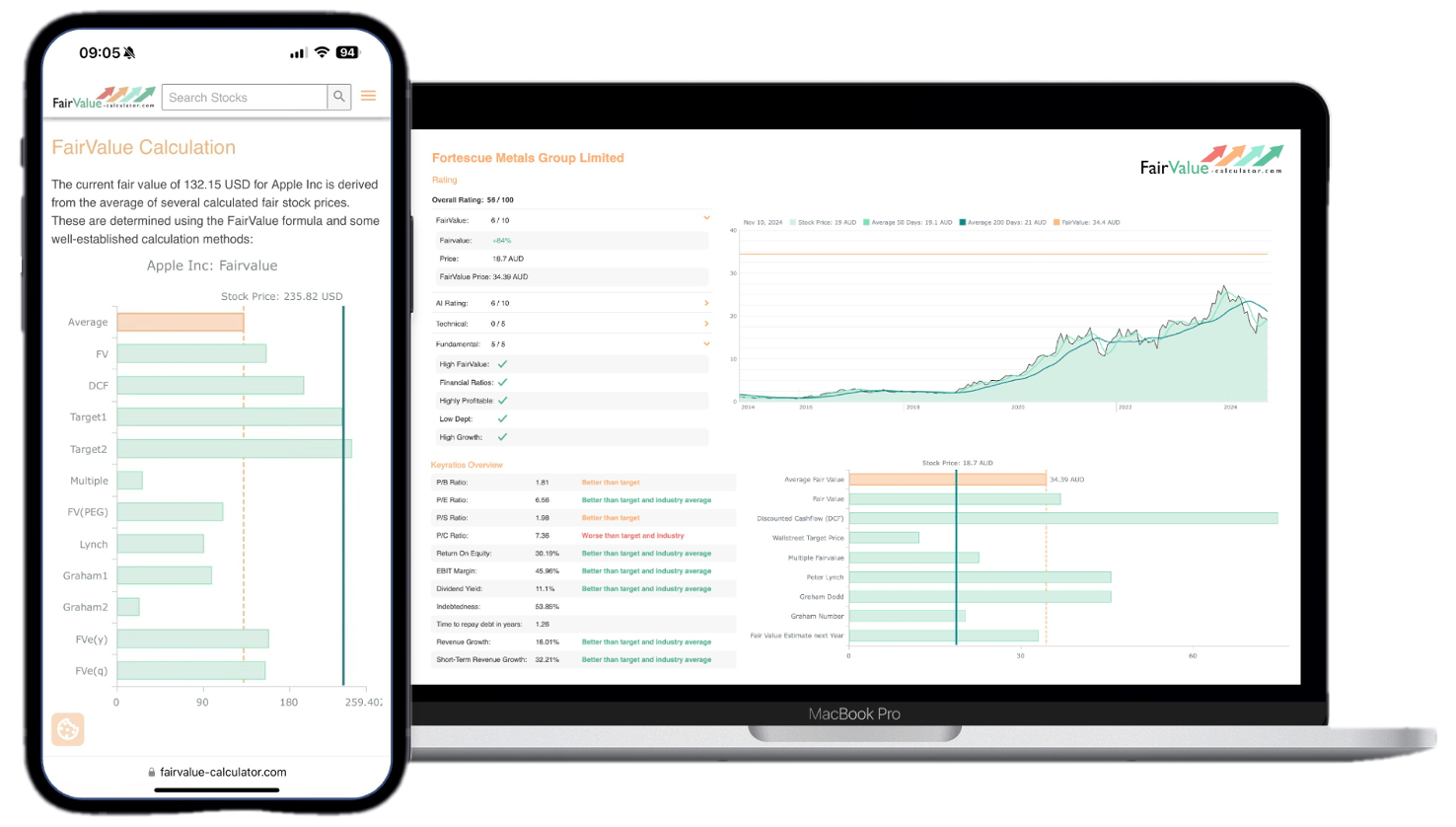

💡 Discover Powerful Investing Tools

Stop guessing – start investing with confidence. Our Fair Value Stock Calculators help you uncover hidden value in stocks using time-tested methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Benjamin Graham’s valuation principles, Peter Lynch’s PEG ratio, and our own AI-powered Super Fair Value formula. Designed for clarity, speed, and precision, these tools turn complex valuation models into simple, actionable insights – even for beginners.

Learn More About the Tools →Limitations of DCF Model

Despite its theoretical rigor, the DCF model has inherent limitations. Its reliance on forecasts can introduce significant estimation risk, especially when projecting cash flows for startups, cyclical businesses, or companies undergoing structural changes. The farther into the future forecasts extend, the greater the potential for error. Similarly, determining an appropriate discount rate, such as the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), involves subjective judgments about risk premiums and capital structure.

Another drawback is the sensitivity of terminal value, which often constitutes a large portion of the total DCF valuation. If the terminal growth rate assumption is overly optimistic or conservative, it can skew the overall value significantly. Additionally, DCF may undervalue companies with intangible assets or optionality, such as patents, brands, or management flexibility—because these factors are difficult to quantify in cash-flow terms. Therefore, while DCF provides a robust baseline, it must be used in conjunction with other valuation models to frame a comprehensive perspective.

The Comparables Approach

The Comparables approach, also known as “comps,” evaluates an asset’s fair value by examining valuation metrics of similar companies or transactions. Instead of forecasting cash flows, this method looks outward to market data, such as price-to-earnings, EV/EBITDA, or price-to-book multiples, to infer a reasonable valuation range. By anchoring value to actual marketplace transactions, comparables reflect prevailing investor sentiment and industry dynamics.

Comparables analysis shines in industries with abundant, transparent peer data and standardized financial reporting. For merger and acquisition advisors, investment bankers, and private equity firms, comps offer a quick, market-driven check against more detailed intrinsic valuation models. However, the success of this approach depends on identifying truly comparable companies and adjusting for differences in growth rates, profitability, size, and capital structure. When executed correctly, comps can validate or challenge DCF estimates by providing an external market perspective.

Fundamental Concepts of Comparables

The core idea behind comparables is that similar assets should trade at similar multiples of fundamental metrics. For public companies, commonly used multiples include price-to-earnings (P/E), enterprise value to EBITDA (EV/EBITDA), and price-to-sales (P/S). Analysts select a peer group, calculate these multiples, and apply the median or mean multiple to the target’s metrics to derive an implied value. Adjustments may be made for size, growth, margins, and geographical exposure.

Comparables leverage market-driven data, thereby embedding forward-looking expectations and risk sentiment into the valuation. This external benchmark approach can serve as a sanity check on more theoretical models. By comparing multiples across time or against historical averages, analysts can also gauge whether a sector is currently trading at a premium or discount, adding another layer of market intelligence to the valuation exercise.

Advantages of Using Comparables

One of the primary advantages of the comparables method is its simplicity and speed. Rather than constructing detailed cash flow models, analysts can generate valuation ranges by referencing readily available market multiples. This efficiency makes comps particularly appealing in deal sourcing and preliminary valuation screenings.

Furthermore, comparables inherently reflect market sentiment and industry trends, capturing the collective wisdom, and sometimes the irrational exuberance, of market participants. This real-world orientation helps ensure that valuations stay tethered to actual transaction prices, reducing the risk of relying solely on internally derived assumptions. In scenarios where market multiples are stable and peers are truly comparable, comps can produce valuations that align closely with transaction prices and secondary market valuations.

Drawbacks of Comparables Method

The primary challenge in comparables analysis lies in selecting a truly comparable peer set. Differences in growth prospects, business mix, margin profiles, and accounting policies can distort multiples. Analysts must adjust for these factors, which introduces subjectivity and potential bias. Overlooking a key difference, such as recurring revenue percentage or off-balance-sheet liabilities, can lead to misleading valuations.

Additionally, market multiples can be driven by temporary cycles, macroeconomic sentiment, or speculative dynamics. If a sector is in the midst of a bubble or downturn, comps will reflect those distortions. Unlike DCF, which isolates a company’s cash flows, comparables lack a mechanism to separate intrinsic performance from market noise. Therefore, while quick and intuitive, comps often require corroboration through other valuation approaches.

The Asset-Based Model

The Asset-Based model underpins valuation by focusing on the fair value of a company’s underlying assets and liabilities. Rather than forecasting future earnings, this approach values each balance sheet line item, tangible assets like property, plant, and equipment, as well as intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and goodwill. The net value is calculated by subtracting liabilities from asset values, yielding an equity valuation grounded in present conditions.

This model is particularly relevant for asset-heavy industries, real estate, infrastructure, and natural resources, where tangible asset values dominate. It also serves as a liquidation or breakup valuation, establishing a floor for equity value if a company were to cease operations. By anchoring the valuation in current market values of assets, the asset-based approach provides a conservative perspective, often used as a cross-check against more optimistic income-based models.

Key Aspects of Asset-Based Valuation

The asset-based approach typically begins with identifying all significant assets on the balance sheet and assigning fair market values to each. This process may involve appraisals, replacement cost analyses, or quoted market prices for securities. Liabilities are similarly remeasured to current settlement values. The difference between total asset value and total liability value represents the equity value from an asset-based perspective.

Crucially, intangible assets, such as intellectual property, brand recognition, and customer relationships, require careful estimation or may be excluded if reliable valuation methods are unavailable. Tangible asset valuations, on the other hand, can often be corroborated by recent transactions or independent appraisals. This rigorous, item-by-item approach yields a transparent valuation anchored in observable market data, though it may underestimate the value of going-concern synergies or future growth prospects.

Benefits of the Asset-Based Approach

One key benefit of the asset-based model is its conservative nature. By valuing tangible assets at market levels and acknowledging liabilities explicitly, this method establishes a reliable floor value for equity. In distressed scenarios or liquidation analyses, it offers a clear picture of recoverable value, aiding lenders, insolvency practitioners, and risk managers.

Additionally, the asset-based approach is relatively straightforward when reliable market data for assets and liabilities exist. Appraisals for real estate or equipment, quoted prices for securities, and well-defined liabilities provide a solid foundation for valuation. This transparency can be reassuring to stakeholders who prefer value estimates grounded in observable market transactions rather than subjective forecasts.

Challenges with Asset-Based Model

A fundamental challenge of the asset-based model lies in valuing intangible and hard-to-measure assets. Brands, customer goodwill, workforce expertise, and synergies from ongoing operations often elude precise valuation. Excluding these elements can lead to materially understated valuations, particularly for service-oriented or technology companies whose value is driven by intellectual capital.

Moreover, the asset-based approach may not reflect the value of operational leverage or growth potential. Companies with high return on invested capital, strong competitive advantages, or scalable business models can command multiples far above their net asset values. Relying solely on an asset-based valuation could underappreciate these dynamics, making it an incomplete picture when used in isolation.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Fair Value Model

No single valuation model reigns supreme in every situation. The comparison of fair values by different models (DCF vs comparables vs asset-based) reveals that each approach brings distinct insights, assumptions, and potential biases. DCF excels in capturing forward-looking cash generation, comparables anchor value to market sentiment, and asset-based models offer a conservative floor based on tangible resources.

In practice, combining multiple methods and triangulating results often yields the most balanced valuation perspective. By understanding the mechanics, strengths, and limitations of each model, analysts and investors can craft nuanced valuations that withstand scrutiny from diverse stakeholders. Ultimately, the right choice depends on the asset’s characteristics, data availability, and strategic objectives guiding the valuation exercise.